WATER DREAMINGS: A VISUAL MAP OF WATER HOLDING PLACES

Stories inspired by being there.

LB-1 ICEBERG CALM Gerlache Passage, Antarctica

We no longer hear shards of ice hitting the hull of our sailboat. After two weeks of loud wave slaps in the Drake Passage and then sharp crunching of ice floes along the Antarctic Peninsula, the absence of sound is a state of grace. We are floating in a vast berg cemetery, where during the brief polar summer hundreds of ice mountains become grounded in a shallow bay and die a slow ice death: they melt, break apart, disintegrate, and the low cloud ceiling is a befitting funeral shroud. Yet these bergs can still overturn -- so suddenly you are always startled -- and roll tons of hard ice into the waves of their own making, threatening everything which happens to be too close. Carefully, we approach an immense icy artichoke with towering petals of cliffs and an eroded turqouise grotto deep in its heart, turn off our diesels and watch a waterfall draining ice melt from the cave. The sound of the gushing stream is lost in overhanging ice cornices, but there is a dim blue glow pouring from the opening above, the first glimmer of light visiting the innards of this chunk of glacier in many centuries of its icy darkness.

LB-2 CROCODILE LUNGE Gnu herd, Masai Mara, Africa

After long rains abate in East Africa, a string of dry days and hot winds sucks moisture from every stalk of grass in the savanna, and the grass becomes ash-golden and brittle. As forage disappears, huge herds of gnu antelope shake their shaggy manes and curved horns which make them look like prehistoric cave drawings, and begin a long march north from Tanzania's Serengeti Plains to Kenya's Masai Mara, in search of water and food. This is a long and perilous journey, since their bodies are food for lions and cheetahs, leopards and wild dogs, hyenas and vultures. And -- crocs. Lying in wait near Mara River crossings and resembling deeply grooved submerged logs, the crocs lurk motionless. Then they charge in one explosive lunge, aiming at the nearest animal trying to enter the river. We wait as well, and suddenly see a large gnu at the margin of the herd becoming airborne even before we sense the croc parting the silty water near its hooves. A miss, which means one life spared for a while and one more still hungry croc, now sinking to the bottom of the swift brown current and beginning his wait again. Here the river means life and death, inseparable and entwined.

LB-3 GRIZZLY CUB Alaska Peninsula, Alaska

His fur is so blond we call him Snowflake: a young grizzly cub, born in the darkness of winter in a snowy den on the Alaska Peninsula. A single cub trailing his mother, with all his litter mates gone -- we will never learn how they perished -- is bored out of his young bear's wits. So, anything new is of high interest: a piece of string and a plastic jug found on the beach are good enough for an hour or two, but then -- what? He still nurses, so he does not need to forage much. He sleeps when he wants to, often sprawled on the warmly furred rump of his powerful snoozing mother. He plays with her when she lets him, but she must graze on succulent sedge plants to make up for her winter weight loss, and cannot just frolic. So, how about the river? The nearby sea pumps the channel with surging high tides and later sucks the water out, leaving exposed gravel bars and small round rocks. The cub carefully selects a stone, black and shiny, picks it up and then drops it with a toss of his head. He hunts it down in the current, picks it up, and tosses it again and again. He bites it. He spits it out. He rolls it with his nose along his raised paw. He plays with his river toy, and plays, and plays.

LB-4 ASHOKAN ICE Catskills, NY

We watch a dance of fresh powdery snow and wind: the snow falls, the wind swirls and pushes it around, and molds it like clay. If the dance happens on a patch of clear blue ice, patterns form and tell a story of the wind's velocity, direction and -- this is not a trite concern -- friction of the ice. We see the shapes of the dance in the narrow sickles of snow scattered on a frozen lake, and wonder. What stops it from blowing right across the Ashokan Reservoir, dropping down the spillway, skimming over the black rocks of the Esopus Creek and, one day in spring, landing as water molecules under a lilac bush? Or a white pine? Or, better yet, in a wet hollow, full of ferns?

LB-5 CAPE PIGEONS, ICE HOUSE Polar Front, South Atlantic Ocean

From afar, we see blue cliffs of an iceberg, a house with tall windows, massive columns and wide smooth porches. It is a floating sculpture in the polar sea, resembling a monumental museum piece with a don't touch warning. We sail closer and see it is a house under surveillance. Scores of Cape pigeons fly by and over and around it, so close their speckled black and white wings must feel the cold breath of ice. When hungry, they alight on the sea and paddle with their webbed feet to disturb planktonic crustaceans they catch and swallow. And any ice mass floating in the Southern Ocean is not just a decorative passive element of the seascape: it is a bountiful Hilton, supporting communities of seabirds and supplying nutrients for aquatic life. Its wake is rich in phytoplankton organisms, these base-building blocks of the food web fed by fresh water of the melting bergs and sediment deposits of trapped terrestrial materials released far out at sea. Phytoplankton loves it all, and it attracts crustaceans which attract fish and whales and seals. So our ice house is a moveable pantry, with the submerged prow stirring up the sea.

LB-6 GENTOO PENGUIN Antarctic Peninsula

Come summer, and ice floes drifting along Western Antarctic Peninsula erode and melt, often forming fluted mattresses used by fishing penguins who jump on them to have a look around. And, if the moment moves them, to vocalize. The call of a Gentoo penguin is a fusion of a dog growling, a goose honking and a small chainsaw biting into a thick oak, but as we listen closely we also hear a braying donkey and the construction of the call reveals its inner rhythm. Loaded with intensity, it pulses with every breath and carries far. We want to climb on the floe near this tall bird with a spotless white chest and a ruby beak suffused with breeding season hues, breathe his clear fishy smell, and listen to the calls which carry way out over the cold, cold ocean.

LB-7 ELEVEN SPECIES OF BIRDS Lake Nakuru, Kenya

Deep in the Rift Valley lies a shallow soda lake, surrounded by wooded grasslands brimming with life. We linger on a nearby cliff, uneasily eying an aggressive baboon troop occupying the warm rocks near us, and watch the surface of the lake. It shimmers pink and white, as huge flocks of resident flamingos and pelicans wade, swim, fish, and fly. In the evening, their energy spent, the birds descend on a small freshwater tributary and use it for washing off the lake's salts, drinking, socializing and resting. The pelicans arrive silently, with their heavy white bodies soaring on narrow wings, and splash among other bathers. Much flapping follows, with the birds turning and dipping and diving, a Maytag of cleaning frenzy. We count 11 species of birds, with Great white pelicans occupying the center stage, Greater and Lesser flamingos, Marabou storks, and Steppe and African fish-eagles crowding the backdrop, and Egyptian geese, African spoonbills, Grey-headed gulls, African sacred ibises and Black-necked stilts waddling, pecking, and meandering in between. On the lake's far shore, Nakuru --the third largest city in Kenya -- hums with intense human bustle, while here tens of thousands of wings flap, tails wag, and feet move in the ancient rituals of birds getting ready to sleep. It is their planet, too.

LB-8 ROCKY RIDGE, SMALL STREAM Sloan Gorge, Woodstock, NY

Take a look around, they say, and we must swivel our heads from here to there, so our eyes -- the eyes of a predator, placed close together and staring ahead -- could take in the whole of the landscape. In this 360 degrees panoramic image of Sloan Gorge nature preserve near Woodstock, NY, we see what a deer can observe with its eyes on the sides of the head or an insect equipped with its wealth of multiple eyes: scan the entire habitat. We behold maples and yellow birch, beech and hemlock, rocks and lichen, and then dive under green hues of June canopies of hardwoods spreading over massive bedrock ledges. Thin seasonal streams, smelling of decaying leaves, soak mossy cushions and fill dark vernal pools hidden among bluestone slabs. The gorge, cooled by the trees and rock cliffs, shelters us from the heat of the summer. We look around, and the woods calmly close the circle.

LB-9 CIRRUS FLOCCUS Kaikoura Peninsula, New Zealand

A rocky shelf of the peninsula juts into the sea off the northeast coast of New Zealand's South Island. The massive wedge forces passing sea currents to surge toward the surface from the shadowy depth of nearby Hikurangi Trench, and the upwelling brings up a multitude of marine life, from crayfish to seals, dolphins and whales. On a low gray evening the sea runs toward the shore in heavy lead-colored waves, and light feathery clouds above unfold like an ostrich fan. The air between the ocean and the coastal Kaikoura mountains is thick with mist, and the clouds move slowly toward the deeper water and the distant curve of the horizon.

LB-10 NOSE Southern elephant seal bull, South Georgia Island

Yes, a nose. Strategically positioned just above the surface, this fleshy trunk-like periscope with two mobile nostrils delivers oxygen to a Southern elephant seal bull resting its enormous bulk of muscles, bones and blubber in a shallow bay of South Georgia Island. But the nose is not just the organ facilitating his breathing. Filled with cavities which reabsorb moisture released during exhalations, the nose will allow the bull to survive long weeks of the mating season without leaving the beach to drink. The inflatable snout can also produce deafening roars, designed to frighten competing bulls and keep them away from the beach master's harem of females.

LB-11 FISH MIGRATION Sockeye salmon, BC, Canada

We arrive on the banks of the river in October to see the biggest sockeye salmon run in North America in the last hundred years. Bordered by the dark forests of British Columbia and rippling with rapids, the river turns red with dense rafts of fish battling the swift current, skirting massive boulders, and resembling garlands of leaves set afloat by sculptor Andy Goldsworthy. The wild salmon swim upstream in large multilayer groups, swirl around eddies, slither under logs, flap in green channels overgrown with forget-me-nots, and jump to gain more speed. Red bodies slice the river with green heads pointing upstream toward their spawning grounds, their pulsing rhythm undaunted and unstoppable. The run lasts several weeks, and then sockeye spawn and die. Their bodies, carrying phosphorus and nitrogen from the Pacific, fertilize the watershed and feed countless plants and animals. But the run, estimated at 35 million fish, catches everybody flat-footed: after 20 years of catastrophic decline of salmon stocks in the most abundant fishing waters of Western Canada, no one had expected it. Not the scientists on both sides of the Canada-US border, who manage the fish stocks jointly and whose computer models failed to predict the record run. Not the commercial fishermen who in the last three years had to tie up their salmon boats but are suddenly filling their holds and running out of ice. And not the environmental community, accustomed to the salmon stocks getting steadily worse. No one knows.

LB-12 ICE, CLOUDS, SEA South Georgia Island

The storm clears and we climb on deck, fastening our parka hoods. The cold front is upon us and after days of dark turbulence the polar air is suddenly clear and translucent. The sea is running high and we are surrounded by a multitude of sails: billowing cumulus clouds with their thick gray and purple bodies, all moving east. And -- icebergs, all sailing in the same direction. Some are skirting the faraway horizon but the nearest one is so close we can see the powdery snow plastered to its surfaces. Yet it is the blue of its hard-packed layers of ice which takes our breath away. For a while, we sail side by side, driven by icy currents and strong winds.

LB-13 MIGRATING SANDPIPERS Bay of Fundy, NS, Canada

Alerted by a familiar shape of a peregrine falcon, the small birds explode from a dull gray beach in a soaring firework of fluttering feathers. Yes, there are dark eyes and short beaks and narrow wings, but it is the speckled pattern of feathers which spreads wide above the surf of the Bay of Fundy. The birds, mostly Semi-palmated sandpipers, flap furiously above the waves tinted by the reddish mud churned up by the advancing tide. They feel safer in the multitude of many. But soon they must land and catch some rest before the tide recedes and exposes Fundy's mud flats, the birds' aquatic pastures studded with tiny crustaceans. In the next week, the sandpipers have to double their weight to continue their fall migration to South America, lasting three days and three nights. So the flock of birds moves on, seeking a safer beach where they can land, hurriedly tuck their heads under the wings and rest, however briefly.

LB-14 COLORADO RIVER, SUNDOWN Grand Canyon, AZ

The river below is full of red silt. It cuts through the sandstone trough of the canyon like a machete blade. Slowly, we climb down large sedimentary blocks balancing on the canyon's rim and still warm from the day in the sun. There is no one around: few people come here because of the rugged access trail, which forces 4x4 vehicles to groan and splutter. We look down, and a darkening chasm beckons with a devilish temptation: fear not -- jump and spread your wings -- fly in the dry desert air among these rock castles, buttes, and towering cliffs. We look up, and the cumulus clouds boiling in the evening light settle us gently back in the safe gravity of the warm rocks.

LB-15 JACOB'S EDIBLE FLOWERS Hudson Valley, NY

When warm weather comes, Jacob gets up way before sunrise and walks down the furrows of the organic garden on his grandfather's farm on the Wallkill River. This is his plot of land to do with as he pleases, and the tidy rows of young salad greens are all his. He also grows edible flowers on their own beds, their bright heads now heavy with dew. Placed in clear plastic baggies on top of generous handfuls of the organic salad mix, they entice buyers at a local farmers' market. But first, they are washed, and as they float in the water they take on the wet sheen of aquatic blossoms, bursting with color.

LB-16 RIVER AFLAME Roundout Creek, High Falls, NY

During the day, not much happens along this rough stretch of the Roundout Creek. The stream flows from its headwaters on Rocky Mountain in the eastern Catskills, passes near Witch's Hole State Forest, follows south into Rondout Reservoir, and enters the valley along the Shawangunk Ridge. Here it leaps down a steep chute near the village of High Falls and flattens out for a while. There are wet boulders slicing the current, a patch of mixed forest and a small hydro-electric dam spanning the falls above. The creek reveals the browns and the grays of its bottom, a modest body of water good enough for a dip on a hot day but not spectacular. But on a sunny fall evening the current fills with the deep hue of the bluest sky, and the most fiery reds and yellows of sugar maples lining its course. The colors explode, linger for a while, then deepen, darken, and fade into the night.

LB-17 REFLECTIONS: RED ROCK AND SKY Virgin River, UT

Utah's first wild and scenic river, the Virgin springs from a Navajo Reservation in Dixie National Forest, runs 160 desert miles across Utah, Nevada and Arizona, and ends in the Colorado River. Along the way, it splits, and the North Fork dives into deep Zion Canyon and nourishes a dense growth of grasses and trees along its banks. Hiking along its edge early in the morning we watch the current turning red and gold and dark blue. The gold patches reflect steep sandstone canyon walls and the blue streaks repeat the clear dome of the sky. The surface glistens with a hard gloss of hammered metal sculpted by a distant fire, but the current makes it swirl and move and turn, never repeating the same pattern.

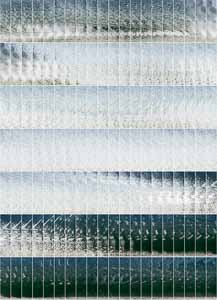

LB-18 SHATTERED ICE Ashokan Reservoir, Catskills, NY LB-19 FOX TRACKS Ashokan Reservoir, Catskills, NY

A skin of smooth new ice spans the Ashokan Reservoir in the Hudson Valley from shore to shore, and holds it fast. Then one night the wind rises from the chilly North and slams the ice against the opposite shore, shattering it into thousands of irregular shingles several inches thick, with edges reflecting the light. And then the current comes and dances around in the dark turbulent water of the lake, pushing and pivoting the ice chunks until they fall into a vast mosaic of patterns, upturned, stacked up, twisted and geometrically perfect, and the last ice splinter settles with a barely audible groan into its place and becomes still.

One morning we notice this hushed icescape during our customary walk along the lake. We begin to photograph it before sunrise when the blue shadows of night paint the ice indigo, and at sunset with the sun sailing low, and on overcast days when the shapes soften and begin to resemble bird feathers tossed on the water. And every day, after following the patterns with our lenses, composing their interconnectedness and making it our own, we worry that the warm weather may return, chew up our ice mosaic and let the wind scatter it everywhere, irretrievable.

But it is a very cold January, and every day we find the ice patterns still there. Sometimes, a bald eagle skims the air above them, calling in its high-pitched plaintive voice of a small bird trapped in a big body. Or a friend comes along and exclaims: this is so beautiful! and we feel as if somehow this spectacle were of our creative doing.

Then the change begins, and the edges of upturned ice shingles become smoother and rounder. One morning the snow falls, thin and granular, and makes the landscape less defined, a new territory of smooth swirls and barely discernible ravines, with a fox leaving its overnight tracks along the edge. Heartbroken at first, we photograph it anyway, hoping that our multi-framed images may capture the flow of the ice, the snow, the wind, the current, and animal life passing through.

When the spring thaw comes in March, the mosaic of ice begins to fall apart and soon greenish streams of the warming lake water scribble the surface. The sunlight thickens and embraces. The clouds above the lake stand tall and full of moisture. The tree branches begin to sing in the wind instead of crackling in freezing air. We flow with the change and watch the ice flow, too, and become the lake again, its winter patterns frozen in our photographs.

LB-20 CLOUD WAVES Richardson Mountains, Yukon, Canada

We hear the Porcupine caribou herd may cross Richardson Mountains early this year to reach its wintering grounds, so we head for the northern Yukon and there, at the northern extremity of the Rockies, we wait. There are eskers of long gone glaciers, and tundra studded with tall clumps of yellowing grass, and ravens wheeling overhead and talking to us and to each other, but no herd. We look for grizzlies and spot one in a fold of the land chewing on a caribou carcass -- an old straggler? -- but the bear does not want our company and we do not insist. Then the sky swells with dark waves of clouds, rushing from the east and trying to overtake one another: a cloud herd, solid and full of surfing waves, floating over the mountains and choking the horizon.

LB-21 FOREST FIRE CLOUDS BC, Canada

Over the course of its nearly 1,600 miles from Dawson Creek in British Columbia to Fairbanks, Alaska, the Alaska Highway parallels some of the largest undeveloped tracts of land in North America. They are somewhat scarred by mineral exploration and logging but also unfenced, heavily forested, and largely devoid of human presence, with big rivers, Peace, Liard, Teslin, Hyland, Rancheria and Yukon, creating abundant animal corridors full of nutrients. We have been driving all day, watching thin strands of fog softening scraggly black spruce and floating among white aspen trunks. The late sunlight licks the trees and a grouse rises noisily from the ditch, flapping madly away. I want to gather some wild raspberries, but the sky pulls me away: it grows dangerously rusty, with dark puffs of cumulus clouds. The westerly breeze brings a whiff of the roasting sap of conifers. Forest fire, most likely ignited by a single lightening, spreads quickly beyond the ridge and devours the tinder box of dry summer woods, its trail marked in the sky by the spreading fiery hue.

LB-22 LAST LIGHT CLOUDS Andes, Patagonia, Argentina

As wet Pacific air gallops east on the shoulders of prevailing western winds, it climbs steep Andean slopes and drops its moisture along the great meandering divide. Soon, afternoon clouds turn into evening ones and pick up deep maroon hues of celestial shadows and thin hints of red from rays of the setting sun. And beyond their heavy cumulus bodies there is a pale sky, barely blue and so smooth it looks stretched and ironed until the last wrinkle is gone.

LB-23 CLOUD ARROW Andes, Patagonia, Argentina

A lenticular arrow points to the blue, infinite and clear world of light, with no borders and not of our making. The air, forced upward to pass over a mountain ascending from the land below, expands and cools, and the water containing molecules join into this smooth arrow-like shape. No one can catch it, own it, or tame it.

LB-24 BOILING SKYSCAPE Andes, Patagonia, Argentina

It is true we have been photographing clouds for years. As long as we can remember, we watched them form and dissipate, glow with a multitude of hues and roll heavy with storms, move with the wind and stand still for hours. We feel the energy of these vast cloudscapes, towering cumulus formations, iridescent waves of lenticular clouds and feathery cirrus fans. To us, the sky is a wilderness, a celestial refuge. But here in Patagonia we forget it all; it is as if all clouds were born here and entered our lives for the first and the only time.

LB-25 DARK CLOUD Alaska Range, Alaska

This dark cumulus with a faint pink border is standing almost still over the Alaska Range. It is the fall of the year, and almost every day clouds are plentiful but --let's face it -- they are mostly silly in comparison. This is a serious cloud, not to be taken lightly, forgotten or ignored. Obediently, we look and look, until it swooshes hard to the right, rolls over and lumbers beyond the ridge, riding low and heavy with wetness.

LB-26 DAWN CLOUDS Canterbury, New Zealand

A storm came last night, rolling across the plains and howling in the dark, but as the day arises all is forgotten. And there is joy in the tangerine light licking the canopy of the freshly washed sky. Soon the fiery clouds will dissipate and the light will flatten, so this is the time to watch the luminous cartwheels in the sky.

LB-27 CLOUDS, SKY Andes, Patagonia, Argentina

The Patagonian sky is alive with clouds again, and we walk around craning our necks. There is an open cirrus fan, and tiny gold colored cumulus puffs, and some lofty mists burning quickly as the day's heat subsides. What is next? What is to come, and where it will come from?

LB-28 CLOUD MOUNTAIN Andes, Patagonia, Argentina

As a mass of cool and moist air slides over a tall mountain, it often forms its own cloud peak of dense texture, crowned with a perfect cap: altocumulus lenticularis. We are lucky this time: above the cap there is still another, smaller cloud, finely layered and tinged with the shimmering iridescence of ice crystals, a celestial rainbow reflecting the high altitude light.

LB-29 CLOUD SAILS Andes, Patagonia, Argentina

In Patagonia, these rising mounds of voluminous cumulus clouds often form in the afternoon and sail toward the Andes, dipping over the lakes and rising above grassy ridges. They are enormous reservoirs of tiny fresh water droplets, perhaps as many as 350,000,000,000 contained in one cubic foot. Their surfaces reflect and scatter the light, and the clouds look milky and opaque, ready to take on any color bestowed on them: they can turn golden and maroon, green and red, blue and orange. Sailing across Patagonia's grasslands, they appear as light as whipped cream until they reach the great mountains spanning the continent of South America. Then they melt into the fog banks wrapping Andrean peaks, and vanish.

The exhibit will hang through July 2013, available for viewing by appointment.

All images are pigment prints, protected by PremierArt Print Shield coating

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________